The U.S. House of Representatives voted 225-200 on June 20 to legalize the industrial farming of hemp fiber. Hemp is the same species as the marijuana plant, and its fiber has been used to create clothing, paper, and other industrial products for thousands of years; however, it has been listed as a “controlled substance” since the beginning of the drug war in the United States. Unlike marijuana varieties of the plant, hemp is not bred to create high quantities of the drug THC.

The amendment’s sponsor, Jared Polis (D-Colo.), noted in congressional debate that “George Washington and Thomas Jefferson grew hemp. The first American flag was made of hemp. And today, U.S. retailers sell over $300 million worth of goods containing hemp — but all of that hemp is imported, since farmers can’t grow it here. The federal government should clarify that states should have the ability to regulate academic and agriculture research of industrial hemp without fear of federal interference. Hemp is not marijuana, and at the very least, we should allow our universities — the greatest in the world — to research the potential benefits and downsides of this important agricultural commodity.”

The 225-200 vote included 62 Republican votes for the Polis amendment, many of whom were members of Justin Amash’s Republican Liberty Caucus or representatives from farm states. But most Republicans opposed the amendment, claiming it would make the drug war more difficult. “When you plant hemp alongside marijuana, you can’t tell the difference,” Representative Steve King (R-Iowa) said in congressional debate on the amendment to the Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act of 2013.

“This is not about a drugs bill. This is about jobs,” Representative Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) countered King in House floor debate June 20. Massie, a key House Republican ally of Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky and a member of the Republican Liberty Caucus, opposes marijuana legalization but had signed on as a cosponsor of the Polis amendment.

The amendment would take industrial hemp off the controlled substances list if it meets the following classification: “The term ‘industrial hemp’ means the plant Cannabis sativa L. and any part of such plant, whether growing or not, with a delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.” The amendment would allow industrial farming of hemp “if a person grows or processes Cannabis sativa L. for purposes of making industrial hemp in accordance with State law.” Most states have passed laws legalizing industrial hemp, in whole or in part, but federal prohibitions have kept the plant from legal cultivation.

However, the annual agricultural authorization bill subsequently went down to defeat in the House by a vote of 195 to 234. Sponsors of the amendment hope that it will be revised in conference committee, where it has strong support from both Kentucky senators, Rand Paul and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell.

The legislation, originally offered as the bill H.R. 525, was sponsored by Jared Polis (D-Colo.) and Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.), who represent states where voters recently considered ballot measures that legalized marijuana within their states, a fact King pointed out in House floor debate. Voters in Colorado and Washington approved the ballot measures in 2012, but voters in Oregon rejected a ballot measure that would have legalized cultivation of marijuana.

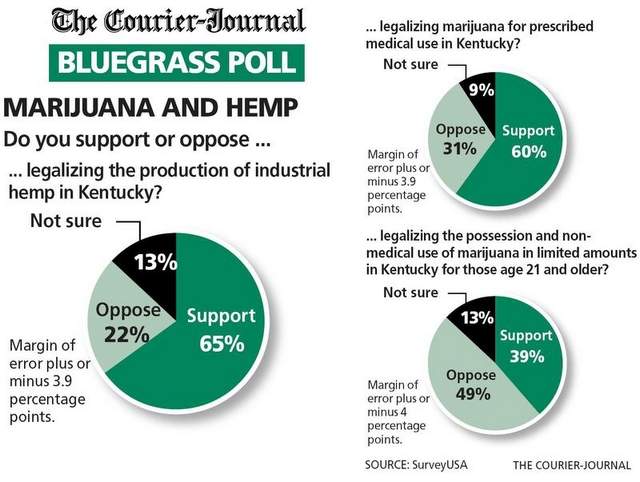

Recent polls have indicated that most Americans want legalization of marijuana, as well as hemp. Though support for marijuana legalization is by only a slim majority of the public, there’s a larger divide among age groups, with younger voters more heavily favoring legalization.

None of the debate on the amendment related to the constitutional authority of Congress to ban substances. Nor did any congressman reference the first time Congress banned a drug — alcohol. At that time, Congress followed proper constitutional protocol to amend the U.S. Constitution first, giving it the legitimate power to ban alcohol (i.e., the 18th Amendment). No comparable constitutional amendment has been passed for hemp, marijuana, raw milk, or any other substance prohibited by the federal government.