America’s environmental laws have influenced the development of green legislation abroad: China’s Environmental Impact Assessment Law, for example, reflects study of the United States’ National Environmental Policy Act, while Beijing’s recent laws and regulations on public disclosure of information show an understanding of the US Freedom of Information Act. Mongolia developed its national environmental laws with the help of American lawyers. There are dozens of other such examples.

But what about environmental case law in the United States? Are there lessons to be drawn from the wins and the losses for counterparts in the environmental law profession and their colleagues abroad?

At a recent roundtable with Chinese environmental law professionals in San Francisco, a lively discussion developed on the issue of lawyers’ fees and court fees. On first blush, this might seem a minor issue compared to the larger environmental challenges at hand both in China and the United States, but in China, public-interest environmental law is so new that working out who pays for lawsuits is still a critical problem to solve.

In the United States, the rule of thumb (often called the “American rule”) is that each side pays its own attorney fees, regardless of whether they win or lose. That’s a critical reason some famous cases – such as the suit organised by Erin Brockovich against California’s Pacific Gas and Electric Company over contamination of drinking water in the southern Californian town of Hinkley – were able to go ahead. (In contrast in England, the risk to the injured citizen of having to pay defendants attorney fees is simply too great and can deter people from pursuing such claims.) Christiansburg Garment Company v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, though not an environmental case, further ensured that when citizen groups lose a case against big corporations in the United States, they don’t have to pay their opponent’s legal fees.

Another key issue for emerging environmental law in China and elsewhere is “standing” – the legal term for the right to sue. In the United States, Sierra Club v. Morton in 1972 was the fundamental Supreme Court case that established standing based on environmental-resource interests. The Sierra Club ultimately lost the case (in which it attempted to fight development in an area near Sequoia National Park, California) but won the war because the Supreme Court decision laid out a clear roadmap for how to successfully establish legal standing-to-sue in future cases. The case established that an environmental organisation could sue not on behalf of the organisation itself, but on the basis of evidence of injury to members whose aesthetic or recreational interests had been damaged.

In 2000, standing issues were further clarified to the advantage of environmental organisations, in particular for pollution cases, as a result of Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw Environmental Services. The case was brought against a company that had formerly been polluting a section of the North Tyger River in South Carolina. The case held that the plaintiffs had the right to sue based on the damage to members who would have used the resources recreationally had it not been repeatedly and illegally polluted by Laidlaw. In other words, the case helped clarify that plaintiffs did not need to produce prohibitively expensive evidence that specific particles of pollution produced by the defendant had specific health impacts on its members.

New laws and regulations on the public right to access environmental information, and efforts to ensure there are legal avenues for making challenges on transparency grounds are at a critical proving point in China, and elsewhere. In the United States, legislation such as the Clean Water Act (CWA) and Freedom of Information Act, has provided clear guidelines on how information must be disclosed, and there have been few modifications by the courts.

Prior to the CWA, for example, the United States’ rivers and harbours protection laws required plaintiffs to prove injury to the environment directly from the defendant’s actions. The CWA put the burden on the defendants by requiring them to file regular “discharge monitoring reports”, detailing whether or not they were meeting their pollution-permit requirements, and creating the right for any citizen or NGO to sue for violations. A company’s own reports must show violations of permits, and the CWA citizen suit provisions have allowed citizen groups to hold companies accountable for these violations.

In other areas of natural resource decision-making, however, access to information on US government decisions has been less clear cut. In 2004, the Sierra Club and Judicial Watch sued vice-president Dick Cheney under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) for holding a series of secret meetings with industry representatives, under the auspices of the “National Energy Policy Development Group”. The plaintiffs were concerned that Cheney was attempting illegally to steer the United States towards a backward, carbon-intensive energy policy and felt that broader consensus on energy issues would be better for the country. Ultimately, Cheney was favoured by the Supreme Court on grounds of protecting state secrets. But the plaintiff’s efforts were hailed as an important tactic for exposing Cheney’s back-door manipulations of national energy policy.

Some US environmental lawsuits are useful to reflect upon not necessarily for their outcomes, but for the tactical issues they raised. Since the late 1980s, a long list of lawsuits brought by various environmental interests targeted protection of the northern spotted owl under the Endangered Species Act and National Environmental Policy Act. These suits first appeared at a time when logging was rampant across the north-western United States, and the cases created a train wreck for the regional timber industry. The environmental side won some of the cases, and lost others. But more importantly, the cases did what the plaintiffs wanted them to do: they greatly raised the profile of the destruction of the nation’s last remaining ancient forests.

The most successful environmental suits in courts, however, are those that are brought as part of a much broader strategy involving public outreach, research, lobbying and other tactics. Environmental lawyers in the United States almost always work in collaboration with environmental non-profit organisations or other citizen groups. One crucial reason for this is that, as president Abraham Lincoln said in 1858, “Public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently, he who moulds opinion is greater than he who enacts laws.” Without public support for a lawsuit, or at least public awareness and concern over the issue it addresses, litigation efforts can backfire. But more importantly, public support is necessary for ensuring that, after a win in court, environmental gains can be sustained over time.

This is perhaps the most important lesson from US environmental case law for new practitioners of green legislation in China and elsewhere, as well as communities and organisations that may seek to bring lawsuits as a means of addressing environmental concerns.

As the professional manufacturer of complete sets of mining machinery, such as Flotation cells, Henan Hongxing is always doing the best in products and service.

New laws and regulations on the public right to access environmental information, and efforts to ensure there are legal avenues for making challenges on transparency grounds are at a critical proving point in China,

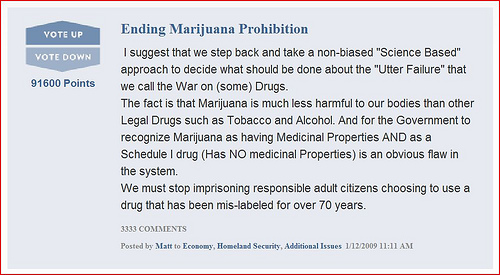

Related Hemp Legislation Articles

After 14 years serving as Deputy Director of NORML under three different Executive Directors, followed by 11 years as Executive Director, Allen F. St. Pierre has tendered his resignation to the NORML board of directors, effective July 15th. St. Pierre, a graduate of the University of Massachusetts, had come to Washington, DC a quarter of […]

After 14 years serving as Deputy Director of NORML under three different Executive Directors, followed by 11 years as Executive Director, Allen F. St. Pierre has tendered his resignation to the NORML board of directors, effective July 15th. St. Pierre, a graduate of the University of Massachusetts, had come to Washington, DC a quarter of […]